Your Psychological Resilience Could Influence How Long You Live

Data from a population-based longitudinal US study of adults over 50

When the winds of change blow, some people build walls, and others build windmills.

-Chinese proverb

Old Tree and Old People by William Gropper. 1939. Oil on canvas. 20 × 22 7/16in. (50.8 × 57 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase. © artist or artist’s estate.Psychological resilience plays a crucial role in promoting physical health by helping individuals manage stress, which is known to negatively impact the biological systems in the body.

Resilient people typically experience lower levels of chronic stress and cortisol, slowing the progression of health issues like cardiovascular diseases and immune suppression.

Such people are also more likely to engage in healthy lifestyle choices, such as regular exercise, healthy eating, and fostering meaningful relationships which enhance overall well-being.

Resilience supports better recovery from illness or injury, as resilient individuals tend to adhere to treatment plans, manage pain more effectively, and generally maintain a positive outlook.

Overall, psychological resilience fosters physical health by promoting effective stress management, healthier habits, and better disease management.

But is there an actual relationship between resilience and how long we live?

In a 2024 study, a group of Chinese and Swedish researchers looked to address this very question.

Starting in the early 1990s, the University of Michigan's Health and Retirement Study (HRS) began recruiting adults aged 50 and older, along with their spouses. The study tracks a broad range of data, including economic, health, marital, and family status, with follow-ups every two years.

Researchers controlled for important factors such as age, sex, race, body mass index, chronic conditions (e.g., diabetes, heart disease, cancer), smoking, and physical activity to isolate their impact on longevity.

Data from 2006 to 2008 was used and followed for mortality outcomes through May 2021. The final sample included 10,569 older adults, with an average age of about 67 years; the majority were women (~59%).

The study used a simplified resilience score (SRS), which was derived from 12 items in the Leave-Behind Questionnaire (LBQ). These items were based on five key psychosocial domains:

perseverance, calmness, a sense of purpose, self-reliance, and recognition that certain challenges must be faced alone.

Key findings

People with higher resilience scores had a significantly greater chance of surviving over the next 10 years, with those in the top 25% having an 84% chance compared to just 61% for those in the bottom 25%.

People with the highest resilience scores had a 53% lower risk of dying during the study, even when accounting for factors like age, gender, and weight.

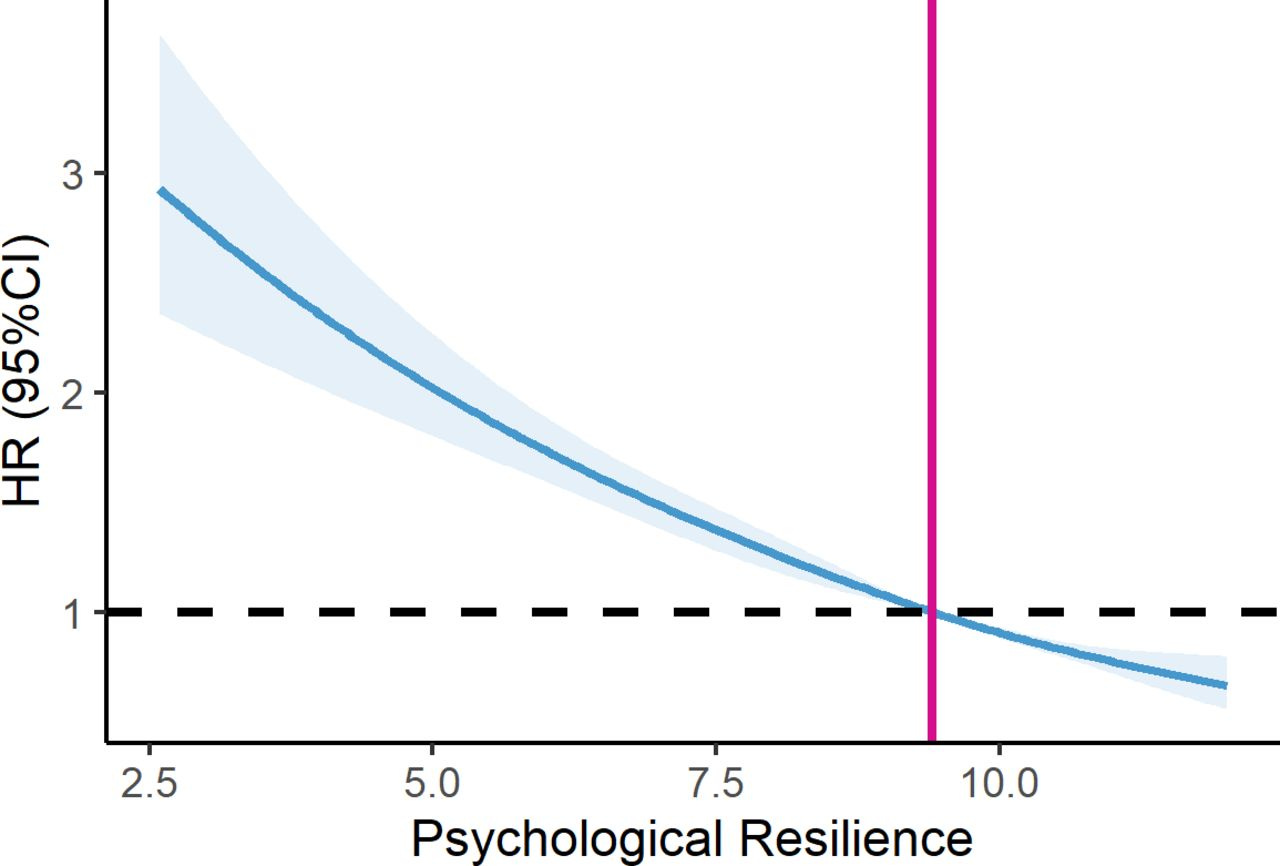

There was a clear, almost straight-line relationship between resilience and survival—meaning the higher a person's resilience score, the lower their risk of dying. There wasn’t a threshold, so higher resilience always seemed to help.

“In the overall population, the higher the psychological resilience score, the lower the observed mortality risk ratio.”The positive effects of resilience on survival were especially strong for people followed for more than 9 years, with the protective effects increasing over time.

The same pattern was found when looking specifically at deaths from heart disease: people with higher resilience also had a lower risk of dying from cardiovascular problems.

Women seemed to benefit more from high resilience than men, with the protective effect being stronger and their risk of death lower at the same resilience level.

Study limitations

The study used a static resilience scale that may not capture the dynamic nature of resilience. This could mean the results only partially reflect the true impact of resilience on health.

As an observational study, causality cannot be established, and the analysis does not account for unmeasured factors (e.g., genetic influences, hormonal factors, or early life adversity) that could influence the findings.

The study's reliance on baseline data also means it may overlook changes in resilience or other factors during the follow-up period, which could affect mortality outcomes.

Takeaways

→People who are better able to handle stress and adversity tend to live longer, with a significant reduction in the risk of death over time.

→This effect is seen across the general population and even more strongly in women.

→Higher resilience not only helps with general survival but also reduces the risk of dying from heart disease.

Importantly, resilience is not a fixed trait but a dynamic process that can be developed and strengthened over time. More on this later..