The German Romantics & Confronting the Uncomfortable

Caspar David Friedrich's work and the role of "willingness" in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

Lately, I’ve been a bit obsessed with the German Romanticism era. Beethoven (who bridged Classicism and Romanticism), Goethe, and Friedrich. Each a giant in their art.

Their work resonates deeply with my work as a therapist: a reckoning with human struggle, a reverence for nature and its natural rhythms, and a willingness to be with discomfort rather than escape it.

Through my work, I like to think my perspective has widened. Having a more panoramic view of life. Identifying what truly matters. Sifting through the noise. Developing a friendlier relationship with internal pain, not through sheer endurance or avoidance, but through an authentic strength. One that acknowledges life’s inevitable difficulties rather than resisting them.

Romanticism, at its core, mirrors this very process.

Romanticism and the Embrace of Discomfort

The Romantics did not shy away from life’s darker corners. They placed them front and center. They embraced loneliness, grief, melancholy; framing these experiences not as obstacles to happiness or contentment but fundamental aspects of the human condition.

This mindset aligns closely with Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), a modern, research-based psychological approach I practice. (ACT is pronounced like the verb, not the initials).

In ACT, we don’t aim to eliminate distressing emotions, thoughts, or bodily sensations. Instead, we cultivate willingness; the intentional choice to approach difficult internal experiences like disappointment, anxiety, fear, and shame, fully, without resistance. The goal isn’t control but acceptance. When we stop battling our pain, whatever form it takes, we free up energy to live according to our values.

This was, in many ways, the Romantic ethos.

The world they inhabited, marked by rapid industrialization and urbanization, mirrors our own era of technological acceleration. In their time, mass farming, factories, and machines reshaped daily life. People flocked to cities, leaving behind rural landscapes and severing ties with nature, and, in many ways, with themselves.

Today, screens, algorithms, and hyper-productivity impose a different kind of detachment.

Then and now, Romanticism offers an antidote: a return to authentic depth, introspection, connection and community, and a radical acceptance of life’s full spectrum of experience.

Caspar David Friedrich: Painting What’s Within

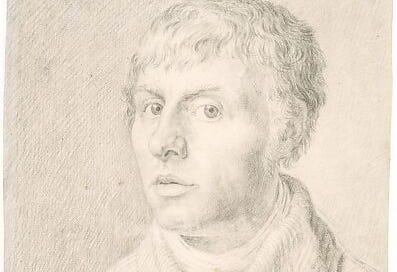

The Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich (1774–1840) captured this sensibility with great depth. His landscapes are not mere representations of nature, they are meditations on the human condition.

The artist should not only paint what he sees before him, but also what he sees within him.

-Caspar David Friedrich

I recently visited Caspar David Friedrich - The Soul of Nature, a major exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. It’s a retrospective celebrating the 250th anniversary of his birth, with over 70 works on display.

Friedrich’s figures, often small and solitary, gaze upon vast, dramatic landscapes, dwarfed by the immensity of the world. His paintings evoke existential reflection, inviting us to confront the insignificance, and simultaneous significance, of our existence.

Take Monk by the Sea. A lone figure stands before an endless, turbulent sky. The composition is stark, stripped of distractions. The vast emptiness mirrors the vastness of inner life; the doubts, fears, and awe that accompany being human. The painting holds space for what is.

Monk by the Sea. 1808-1810. Oil on canvas. 43 5/16 × 67 1/2 in. (110 × 171.5 cm). Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.This echoes ACT’s core principle: rather than numbing discomfort, we turn toward it with openness. Monk by the Sea does not distract us from solitude or uncertainty, it magnifies it, asking us to contact it.

Another example, Woman at the Window (1822), captures a moment of contemplation. The subject is turned away, gazing beyond the frame, into the unknown. Much like the therapeutic process, Friedrich’s work invites us to face and embrace uncertainty, to lean into what we cannot control.

Woman at the Window. 1822. Oil on canvas. 17 11/16 × 12 7/8 in. (45 × 32.7 cm). Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Germany. Friedrich has an ability to bridge the gap between light and darkness. His works speak to complexities, showing how both pain and beauty are interwoven in the fabric of existence. Bittersweetness. Susan Cain writes wonderfully on the necessity of bittersweet experiences in life.

Rocky Reef on the Seashore. ca. 1824. Oil on canvas. 8 11/16 × 12 3/16 in. (22 × 31 cm). Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe, Germany. This perspective isn’t confined to the 19th century. Contemporary artists like Radiohead and Björk channel complex emotions into music, transforming pain into something profound. Films like Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind and The Tree of Life, explore memory, loss, and the search for meaning; hallmarks of Romanticism.

Like the work of Friedrich and other German Romantics, these pieces don’t seek to sanitize discomfort or pain. Instead, they illuminate its depth, revealing beauty in sorrow and meaning in struggle.

In a world that often prioritizes detachment and efficiency, they offer a counterpoint: an invitation to feel thoroughly, to embrace the bittersweet, and to find transcendence in vulnerability.

Even in our hyper-rational, productivity-driven culture, the Romantic impulse persists, offering an antidote to numbing discomfort or chasing relentless positivity.

Questions For Reflection This Week

What if you gave yourself permission to experience difficult emotions, without judgment? How might that change the way you respond to them?

What values matter most to you when you're experiencing discomfort? How might anchoring yourself in those values help you navigate the discomfort?

Like Friedrich’s figures, are you willing to stand before the unknown, not in fear, but with the fear?